I new when i came up with the idea of a short run of Polaroid projects I would eventually get around to Peter Miller; a good friend, fantastic artist, and, as you shall see, an exciting writer and theorist. Though Peter has yet to produce a publication in the form that would usually be featured here, his work is so fitting to be highlighted on this blog in addressing the aesthetics and concepts of the Polaroid image.

Peter’s work is three things; phenomenal, magical, and clever, and, regardless of your personal take on the Polaroid image, you have to admit that these 3 adjectives describe the Land Camera as well.

When I got around to psyching myself up to take on Peter’s work, I decided instead that he would be a great first guest writer. His text is rather long, but not long-winded. I will post it in 2 parts, so come back tomorrow for a second helping.

Thanks for your contribution Peter.

Enjoy…..

On Polaroid: magical mechanics and the altar of objecthood

by Peter Miller

The Polaroid is such a unique and ubiquitous object that it needs no introduction. This is a very good thing, because any introduction would invariable sound histrionic, nostalgic or cheesy and I do not believe that the Polaroid ever aspired to any of these qualities. The Polaroid just wanted to be a photograph, same as any other, except that it wanted to be an instant photograph. In order to become that instant photograph, it had to sacrifice its photographic flatness and join the world of the three-dimensional machines, objects. It is specifically these two qualities that attracted me to my recent work with Polaroids, which I’ll write about here: the magical mechanics of the Polaroid “instant” and the altar of its objecthood.

Magical mechanics

Roughly half of the Polaroid work that I’ve made in the last few years investigates the complexity of the Polaroid “instant”. In order to achieve his goal of instant, or more precisely, one-step photography, Mr. Land decided to divide the entire laboratory between the camera and the photographs themselves. Although this condenses the process of exposing and processing an image into a self-contained chain of events, it does not reduce them to an instant. In fact, in practice each Polaroid requires several noisy seconds to produce while the camera turns itself inside out, and then another minute or so as the image materializes. For anyone curious about all that occurs inside of the camera, Charles and Ray Eames made an exquisite and informative film document for the release of Land’s SX-70 camera that is a lot of fun to watch. So what invariably remain within this instant are a moment of exposure and a moment of development; Land couldn’t get around that, there had to actually be two-steps in his one-step. And there exists a magical space between these two events in Polaroid, whose mechanics is not often thought of. There is a similar magic afoot in the mechanics of a photo booth photo-strip, which are closely related to Polaroid. I have recently been drawn to the potential of this space within the Polaroid instant and have sought to make a series of works that employed its existence and relative invisibility.

For “Nothing Ever Happens Twice A”, I produced two identical Polaroid photographs:

In each Polaroid a figure is seen walking away from the camera, the doubling of the moment is indicated by the figure’s heel striking its own shadow. There are other describable things occurring in the images, but it is this dual shadow-heel event that unifies the two. Duplicity means ‘doubling’, but it also means ‘deceitful’. I intend for there to be something uncanny in these images, something that might make one’s toes curl. Quite frankly, it would be practically impossible to make these images with a Polaroid camera. In fact, I recorded the image on 35mm slide film, enlarged it onto a raw Polaroid in the darkroom and then sent it through a Polaroid camera to process it, thus severing the chain of the Polaroid instant and playing in the space between exposure and development.

The “B Side” to this diptych is “Nothing Ever Happens Twice B”.

In it, one can see an identical chemical error in the upper left corner of two Polaroid photographs, one black, one white. Polaroid cameras have flaws unique unto themselves. I have one that always produces this incompletion, this corner of beautiful image decay.

Fascinated by David Hockney’s Polaroid portraits, I set out to see if I could make my own, but rather than using his technique of seeing a figure a hundred times at once from slightly different perspectives, I wanted to make a cohesive whole, a stained glass version. Again, I wanted it to appear impossible, or at least to not immediately reveal to the viewer, the magic with which it was made.

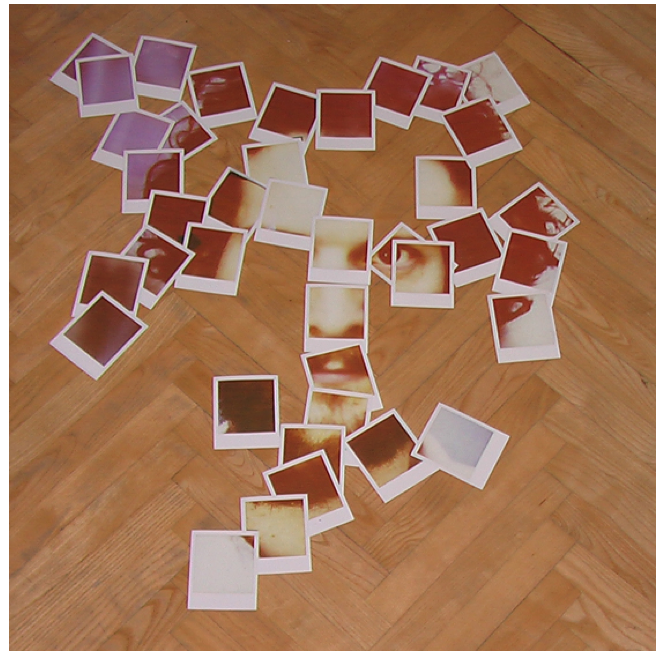

In order to make this “Polaroid self portrait” a grid of 90 raw Polaroid photographs were laid out in the darkroom and a single slide was projected onto them for seven seconds. Then the 90 Polaroid photographs were returned to their packs and one-by-one, with the lens covered, they were ejected by the machine and thereby processed. The portrait took seven hours to make, not an instant. It’s also worth drawing attention to the fact that a Polaroid is a positive. That’s why I projected a slide onto them. The longer the exposure, the brighter they become. Another highly unique quality to this and similar of these Polaroid photographs is that the light creating it never passed through a Polaroid lens. I recorded this original portrait as a 6cm square chrome and projected it using a very high quality enlarger, giving the light over to two very fine lenses. The result is a degree of fidelity, a depth of focus and a macro capacity that was never inherent to Polaroid photography. I hope that these smaller details also amplify the uncanniness of the image. To heighten some of these qualities, I made a second version of this portrait where the images were randomly laid out, not built up in a grid. The resulting piece is called “Gestalt” for the way in which it stitches itself together in the mind of the viewer. It is best shown on the floor so that it appears as random scattering of dropped or thrown photographs, making its totality seem even more impossible.

In these works, as with other of my Polaroid photographs, the potency of the illusion hangs in direct relationship with the authenticity of the Polaroid. Unlike other photos-sensitive papers, each and every Polaroid is a sophisticated object hermetically finished and guaranteed by the standards of today’s factory standards. In other words, none of us could make a Polaroid at home if we wanted to, a problem suddenly facing the would-be post-2009 Polaroid photographer. This authenticity of image may be unparalleled in the history of images. Evidence of this degree of authenticity can be found in some of the popular professional uses of Polaroid photographs. The film industry used them to record details of a set or costume so that they could be matched on consecutive shooting days, avoiding costly breaks in continuity. They have long been a standard technology for producing the highly standardized and exalted passport portrait. They are also popular in the field of justice because they stand up well in a court of law as a piece of evidence. These three formidable industries generally are very well funded and cannot afford error. Through this need for consistency in representation they lend credibility to the Polaroid, that what is contained within the image of its object is something that is real and is something that actually happened. The precious and complex technology that makes up its encasement underscores this realness and makes the Polaroid a particularly interesting site for image manipulation, above all for the manifold possibilities that come about when the credibility of this authenticity is destabilized.

Stay tuned for part 2….”The altar of objecthood”