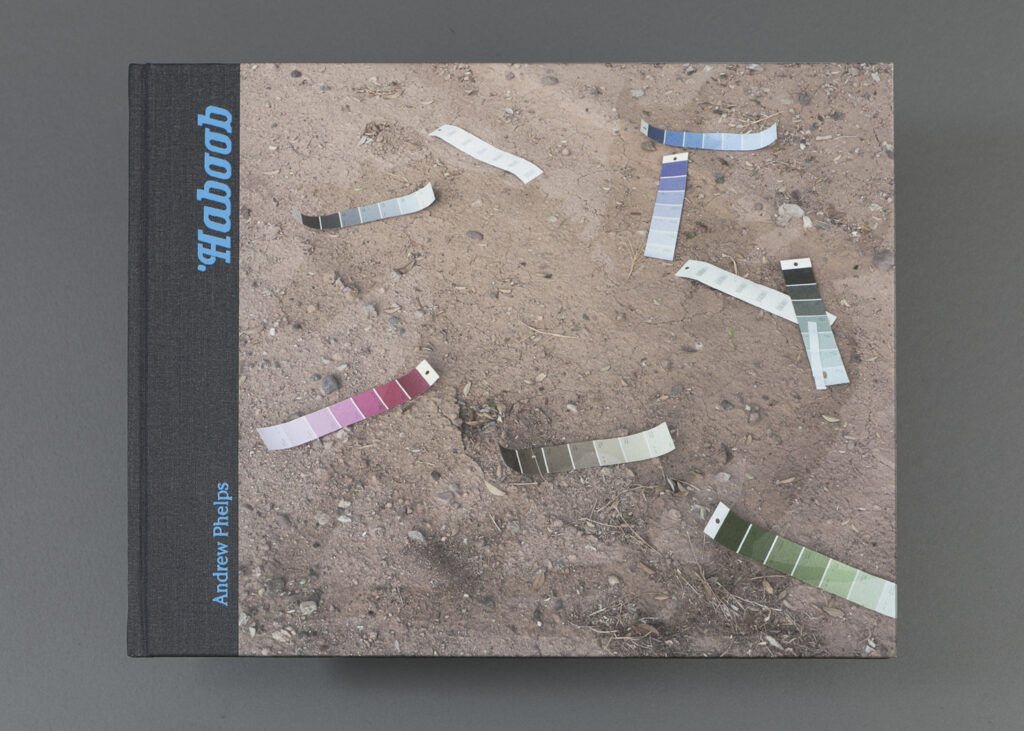

Haboob

2012

28×32 cm. 42 photos.

Gebunden

KEHRER, 2012

ISBN 978-3-86828-345-7

mit einem Text von Leslie Le Roux

HABOOB

ein heftiger und drückender Wind, der im Sommer weht und Sand aus der Wüste bringt. Aus dem Arabischen habüb “wütend blasend”.

Ein Nachfolgewerk von HIGLEY, das 2007 veröffentlicht wurde und den plötzlichen materiellen “Fortschritt” von Higley, Arizona, dokumentiert, einer Bauerngemeinde, die durch den boomenden Wohnungsmarkt des amerikanischen Westens verändert wurde.

Die neue Grenze im Westen ist der sich ständig ausbreitende Stadtrand. Haboob ist ein fesselndes Porträt einer kleinen Wüstenstadt, die im Kreuzfeuer zwischen Bodenspekulanten und Nutznießern der Wachstumsmaschine steht. Das Ergebnis ist ein bildhaftes Dokument von Zivilisation und Barbarei. Andrew Ross, Autor von Bird on Fire: Lektionen aus der am wenigsten nachhaltigen Stadt der Welt

Mehr über das Projekt erfahren: HABOOB.

Scrollen Sie nach unten für ein Interview mit Fabio Severo

HABOOB ON HIPPOLYTE BAYARD

Fabio Severo, Hippolyte Bayard blog, 2013

A follow-up to a photography book is an unusual concept, especially if a project is openly declared as a sequel to another one. Several artists have been developing one single subject matter for a long time, exploring it through different bodies of work and sometimes shaping their whole career around it. But a second instalment starting from where another book ended is a different story, it is as much about expanding a narration as about the artist questioning their own vision; it is a bit like looking at yourself in the mirror.

Andrew Phelps looked at himself, and at his own personal history, by going back to what is probably his most important photographic work so far, and expanding it into another book. In 2007 Phelps published Higley, a book about the fading days of a town which was about to merge in the area of greater Phoenix, ending its life as a separate township. Its zip code officially disappeared in 2007, and with that decades of private memories and treasures of a whole community, including those of all four Phelps’ grandparents, who used to live there. The housing market began to collapse in 2008, and many houses remained unsold, while many others were left incomplete. Phelps went back to Higley to document what happened during that suburban transformation which erased a farming community in order to build another real estate stronghold, a flat dream of single family houses which turned into a pointless form of land grabbing. Haboob is the fruit of this new journey to what was once called Higley.

Haboob is the name of a violent and sandy summer wind, a frequent occurrence in the East Valley, the region of the Phoenix metropolitan area. The Arabic word means “blowing furiously”, and what the book shows looks like the aftermath of a storm, the consequences of the wind of these years’ financial crisis and the crushing of the dreams of the never-ending urban expansion. The area of Higley shown in this new book looks even more deserted and unfinished than the transition documented in the previous work, in which we could witness the limbo where new houses were being populated while old ones were abandoned. Lifeless constructions, neatly packaged interior designs, concrete, debris, and dust: Haboob reminds of somebody wandering in an empty land, trying to understand the few signs of life around him. Only a few photographs show residents of the community, and they always appear like distant creatures, as if the photographer did not dare to go closer; while the previous book had plenty of intimate portraits of men and women, often inside their own houses, and most of the other photographs were still showing plenty of signs of the life those people lived there.

Higley opened with the photograph of a field showing a compact block of houses in the distance, and ended on a group portrait in a backyard, with the blurred figures of a man and a little girl running to join the others. The caption says “Andrew and Leonie scrambling to beat the self-timer for a family portrait. The last day of Higley, 2007”. Haboob opens with a flat TV screen showing the picture of a storm approaching, and ends with the view of a flatland seen through a mist which could be made of sand. It is undeniable that the two books together tell the story of a loss: the signs of life and warmth still present in Higley slowly disappear through the pages of Haboob, perhaps only kept alive by the ghost image of two running horses printed on the cover, taken from a photograph of their silhouette on a welding abandoned on a street.

This is why making a work like Haboob is such a challenge for a photographer: having to face the physical erosion of places belonging to your most intimate recollections, plunging your vision into your personal landscape and then trying to find a way to depict the emptiness left in it.

“More than once, in the last three years, have I found myself at five a.m. in a borrowed car, missing my family, with a box of unexposed film haunting me from the passenger seat, unsure that anything in this now foreign place would ever open itself to me again. Though it is thinning, I still have family in Higley, and when I lose my way and don’t know where to set up the camera, I can always go back and find pieces of myself in this landscape, these fields, this light”.

This is what Andrew Phelps was writing five years ago about Higley. What really makes Haboob remarkable is that with this book he chose to face the risk of not finding those pieces of himself anymore, because that landscape, those fields are now so different from how they used to be. Perhaps what rescued him this time was that the light was still the same, beautiful light he remembers from back then.