Wolfgang Scheppe’s new book Done.Bookis the perfect follow up to his mega project Migropolis from 2009. Where Migropolis examines Venice, Italy’s future as a complex globalized society, the Done.Book dives into its meticulously documented past by two self-proclaimed visual archivists. One, John Ruskin, is very famous. And one, Alvio Gabagnin, a virtually unknown self-taught photographer from the working class of Venice.

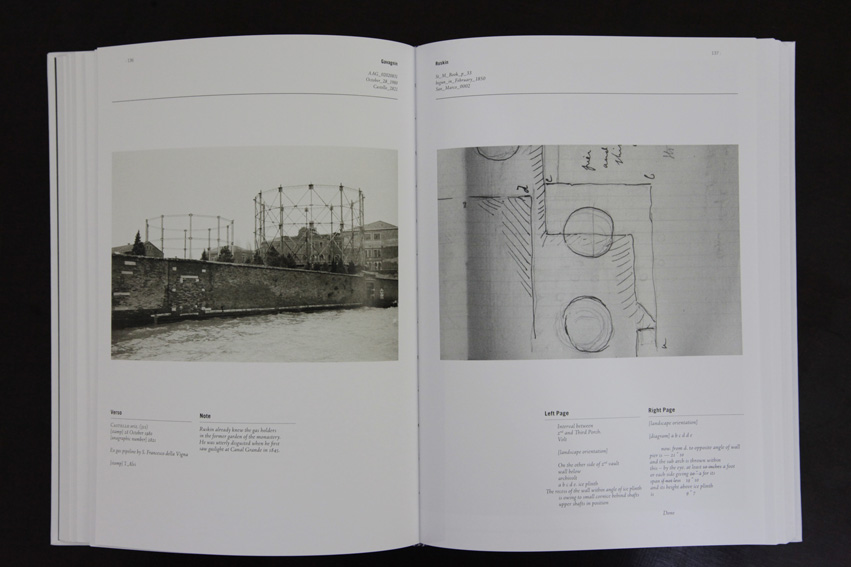

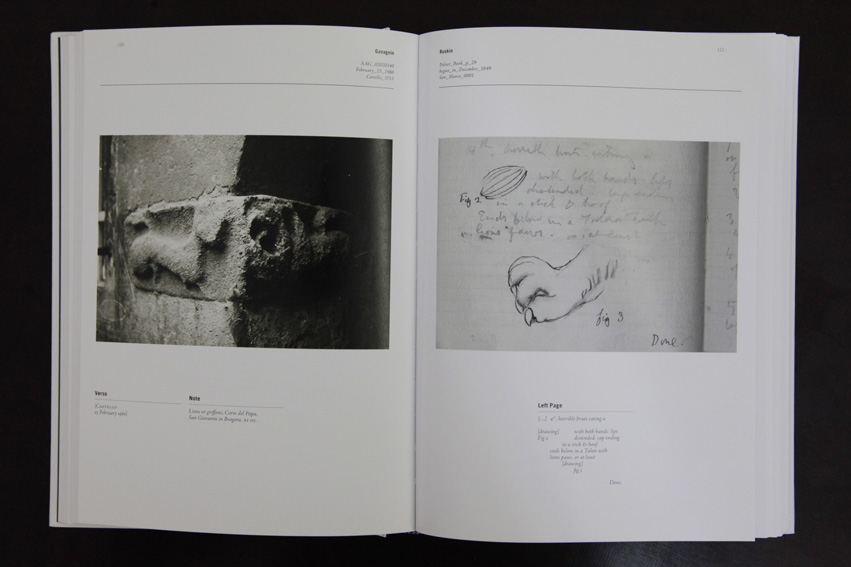

photos by Gavagnin (left) and drawings by Ruskin (right)

The british social thinker John Ruskin spent 2 years from 1851-53 compiling his Venetian Notebooks, an incredibly in-depth visual study of notes and sketches, filling 1240 pages of manuscript describing, in minute detail, hundreds of architectural nuances and social situations around Venice. The complexity of these notes is apparent in the small detail which appears on hundreds of his original pages; a note to himself when he felt a thought or study had been sufficiently worked out – “Done”. It also indicates his struggle to cope with the “…sheer un-manageable expansion of his practice of close looking…”

As Scheppe notes, “he lived in a society that made reference to itself in the written word.”It is safe to say that had Ruskin the chance to photograph, he surely would have reached for a camera. His way of searching and note-taking seems to be a fore-runner for the ideologies of straight photography;

…Ruskin distanced himself from the “confectionary idealities f the then prevailing mode of the picturesque. The projection into the object of subjectivity characteristic of every conventional form of representation he treatdted as a pathetic fallacy, which could serve only to express ignorance of the laws of nature. In contrast to the contrived composition of an idealizing way of seeing, he regarded his own practice of sketching simply as the “written notes of certain facts”…

Wolfgang Scheppe

Fast forward 130 years and Scheppe meets the contemporary equivalent of Ruskin and his relentless collecting of details, albeit in the form of a photographer, the appropriate medium for a contemporary documentarist.

Alvio Gavagnin is a Venetian, born, raised and still resides one of the worlds most complex cities and multilayered societies. Gavagnin and his wife Gabriella have spent the last decades (1960 to late 80S) literally cataloguing and photographing every corner, bridge, building and subtle attributes of the city. The working structure is very rigid, mapped out with the use of city guide books and maps, taking a scientific approach to covering all aspects of the city, yet the images don’t shy away from poetic observation. Admitting it himself, Gavaganin is a fanatic collector, a stickler for organization and detail, and a self-taught admirer of the beauty of black and white photography. The previous works by Scheppe in Venice go so deep into the history and literally invent a visual language to describe the social and political nuances of contemporary Venice. Now, with the discovery of an archive of contemporary photographs of Venice which comes as close to matching the rigorous observation of Ruskin, Scheppe has created an entirely new catalogue of the city.

books by Gavagnin (left) and Ruskin (right)

The heart of the book is a comparison, both aesthetically and contextually of the two projects. Double-page spreads show us one photograph from Gavagnin and one sketch from Ruskin, often the verso of the photos or note cards. The final products of both Ruskin and Gavagnin seem to be small, hand-bound notebooks with remarkably similar dead-pan titles such as “Horse Book, 1983” and “Collision Book, 1979” (Gavagnin) or “Door Book, 1849” and “Palace Book, 1849” (Ruskin).

As a photographer, one of the most interesting aspects of the book for me are the “loading frames” which Scheppe grants equal attention as the catalogued images. These are the first couple of frames which the photographer, when shooting 35mm film, must advance past when loading the film in the camera. These first few inches are exposed in the loading process and to be sure that we start our image taking on a bit of un-exposed film, we aimlessly release and advance, release and advance the film a few times. Scheppe considers these “loading frames” to be the most objective form of image making; the photographer not influencing the outcome of the image, but instead blindly pushing the button at a random angle. We see a piece of the world peeking around the last bit of exposed film, dust and scratches and all, and being that Cavagnin is so efficient and economical in his approach, all of these loading frames were archived on each role.

This book is published by Hatje Cantz as a part of the Villa Frankenstein, the British Pavilion exhibition at the 12th Architecture Biennale in Venice in 2010.

Wolfgang Scheppe might possibly have one of the best home pages out there…give it a look, you may not be there very long, or maybe you spend the day thinking about it.